“as a Service”

As you start your cloud journey, you’ve probably come across a bunch of “as a service” terms, like the previously mentioned infrastructure as a service. When you begin, especially if you are migrating from an on-premises environment, thinking in terms of these “as a service” types will keep you mentally organized.

The three main “as a service’s’s’s” are infrastructure as a service, platform as a service, and software as a service. These terms are abbreviated as IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS. In short, these terms refer to how much in the weeds you are with your infrastructure and how much control you have. So if your organization’s email is hosted on a Microsoft Exchange server that you have running on a virtual machine, you’re using IaaS. If you use Microsoft 365 for your email, you’re using SaaS.

physical router image by George Shuklin, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

There are more “as a service” things, depending on whom you ask. But I’m limiting it to these three, because otherwise where does it end?! I think other aaS’s really fall into one of the broader categories of IaaS, PaaS, or SaaS, anyway.

This may be obvious, but just for clarity let’s talk about the term service. When we talk about a service, we’re talking about the application or program that we want to make available. A service could be a database, web site, or API. It could be something that is used by another service, such as a Redis Cache. A service may be something you install on a virtual machine (VM) or becomes available to you through the magic of the cloud, as we’ll see.

Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS)

Infrastructure as a service means that you are replicating your traditional on-premises environment in a virtual environment. You’re creating a virtual network, deploying a VM, and installing your service on that VM. When you need to make changes to your service, you’ll log into the VM and make changes. Really, the only thing that may be different is that you’re using VMs instead of physical machines.

The benefit to this is that you have total control over your service. If you’re installing SQL Server, then you can completely manage the high availability feature of SQL Server (known as Availability Groups). In fact you’re responsible for everything related to the VM, including patching the server.

The drawbacks are exactly the same as the benefits. In the SQL Server example, you have to manage the Availability Groups, which is something that is very easy to screw up. You have to remember to patch your VMs, which is menial task but one that can have dire consequences if you don’t do it.

Platform as a Service (PaaS)

Platform as a service gets rid of the VM management and simply presents the service you want to manage. So let’s take the SQL Server example in the context of a small, scrappy startup named Scramoose. This company needs a SQL Server, but the engineering team only consists of two developers. Provisioning a VM, installing SQL Server, configuring the Availability Groups, and creating certificates to encrypt the database is a lot of work. Learning how to do this isn’t exactly a useful endeavor for the developers. All they need is the SQL Server.

A platform as a service SQL Server offering would be a SQL Server but without a VM that you can actually log into. For our two developers, this is fantastic! All they care about is a database that they can read and write to. They don’t want to be patching VMs every week, because that’s not going to move their work forward.

Behind the scenes in most cases, a platform as a service product is simply that product installed on a VM but without the VM being exposed to the user. In other cases, it may be more of a “fabric,” meaning that it may be a bunch of services working together to expose only the service you’re interested in. So in the SQL Server example, it may be a bunch of compute services working with a large storage service that represents a gigantic shared SQL service used by several customers that can securely carve out a single database just for you to connect to. The developer shouldn’t need to know or care to know how it all works, and that’s the point. They just get the database and they’re happy campers.

IaaS vs. PaaS

If you’re an infrastructure engineer you’re mostly going to be working in the IaaS or PaaS world, so let’s stop here and talk about when to use each one. As with many decisions, there’s no right or wrong answer, and it totally depends on the situation.

Let’s stick with the SQL Server example and explore the Azure offerings, and let’s assume that we’re going to want some type of high availability (meaning the SQL Server instance will recover if there is a failure). If you go the IaaS route, you can install a few VMs, install SQL Server on them, and use SQL Server Availability Groups to ensure that SQL Server will stay online if a VM goes down. If you go with the PaaS route, you simply request a new SQL Database and the high availability is handled automatically.

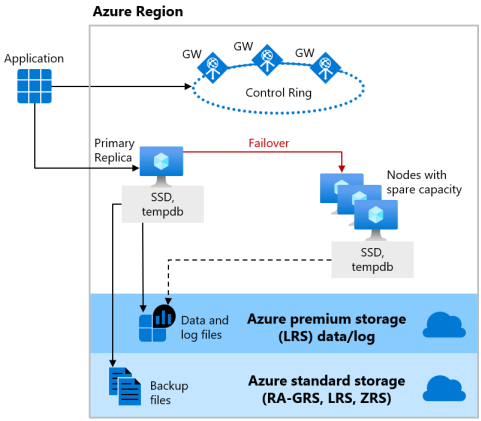

To help - or more likely confuse - here is diagram from Microsoft’s docs showing their PaaS availability for Azure SQL:

Now let’s dig into the details slightly. With PaaS, Azure is going to handle high availability by giving you four nodes (think of this as four SQL Server VMs) as shown by the primary replica and three failover replicas. So if one of the nodes stops working, one of the other three will pick up the load. For most people, this will be more than enough. But let’s say your CTO is a complete freak and insists you have ten nodes. Well, you don’t have that kind of control with PaaS. You’re going to have to install SQL Server on VMs, therefore going the IaaS route.

Here’s another possible scenario. SQL Server has the concept of synchronous/asynchronous replication. In short, synchronous replication means that SQL Server won’t consider data written until all nodes have written the data. You can control the synchronous/asynchronous mode in an IaaS environment and configure synchronous replication even if the nodes are on different sides of the country. This would make your SQL Server slower than you’d probably prefer, but you may have a good reason to enforce this (think finance or healthcare). However, you cannot enforce synchronous replication in Azure’s PaaS offering.

To put my thumb on the scale a bit, I recommend you default to PaaS unless you need a reason to fine-tune your service. In general, a lot of the configuration options are removed for the service when you use PaaS, but those are not likely to be configuration options you’ll ever use. You’ll save yourself time and probably money, too.

Software as a Service (SaaS)

Software as a service is not something you’ll use a ton as an infrastructure engineer but it’s important to know. Usually SaaS is accessed directly by the user on the web. You probably use a lot of SaaS products in your personal life. For example, if you use Gmail you’re using a SaaS product. If you’re working for a software company, you’re probably working for a company that is delivering a SaaS product. Software products that aren’t SaaS would be software you install on your workstation, like the desktop versions of Adobe Photoshop or Slack.

The only time you arguably could be using SaaS is if you connect to a SaaS product as part of an automated deployment. Like, maybe after you deploy a new application, you want to close out an Asana ticket. Connecting to Asana could be considered a SaaS integration.

Pizza and Other Resources

If you don’t like the way I described it, Google has a good description. Warning: it includes containers as a service, which I consider to be a subset of IaaS.

There’s also a commonly used pizza analogy to describe these concepts that was first presented by Albert Barron. David Ng has an update on this analogy that I agree with.

Comments