DevOps and Other Buzzwords

This post is a grab bag of techy words that you should know. Some of them are important, some are not. But all of them are words.

DevOps

DevOps is a broad category that does have an actual meaning but also can be confused with a lot of other things. DevOps is short for development/operations and the point is to remove the barrier between application development and operations/IT/deployment. In the old days, developers would write code, package it up, and throw it over to the deployment team. The deployment team would install the application at 2 AM and then get a call at 3 AM when there was a problem, where they would immediately blame the developers.

DevOps uses automation and a lot of the other buzzwords below to try to eliminate this broken system. For a detailed explanation, see What is DevOps? from GitLab. The rest of the terms in this post are not all specifically part of DevOps but are often used as part of a DevOps practice.

Agile

Agile is a project management approach where you break your work into small chunks that can be quickly performed. This approach stands in contrast to traditional waterfall styles of project management where a bunch of idiot middle managers would dream up an entire project plan over the course of a few a meetings. The problem with this waterfall approach is that you can’t plan all the ins and outs of a project in a windowless room. If you’ve ever worked on a technology project, you’ll find that some or most of your expectations were wrong on day one. So usually, the idiot managers get it even more wrong.

With Agile, you still have a product goal, but you only define a small chunk that you can do next. So if you’re building a new web-based video game, the first chunk you might work on is the welcome screen. It won’t do much, but it will be a minimal viable product (MVP) that will at least work. Then you keep updating the product - feature-by-feature - always having a working MVP.

Agile is not a prescribed project management style, but rather a philosophy. In fact, it’s really just twelve principles. Agile is a very good thing if you work at a place where people take it seriously. Agile generally comes in two flavors: Scrum and Kanban. The details are beyond the scope of this post, but it’s something you should research and decide as a team how you want to approach your Agile style.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure simply refers to the resources that you’ll be deploying to your cloud environment. Every time you create, change, or delete a resource, you’re changing the infrastructure.

Infrastructure as Code

Infrastructure as code (IaC) is a way to define your cloud infrastructure using text-based files. IaC is the main thing this whole blog is about, so I have a whole section about it: Infrastructure as Code.

Source Control

Source control is where you store your IaC files, which is covered by the Git post.

Continuous Integration & Continuous Delivery

Continuous integration and continuous delivery are two different concepts used together to refer to the process of incorporating changes you made to your IaC files in your source control so that the changes take effect in real life. So let’s say you update your IaC to add a web server. You’ll make those changes on a new Git branch so that you don’t mess up the main branch. The CI/CD process will gracefully merge those changes with the main branch and then create that web server you defined in IaC.

Honestly, I find the distinction between the CI and CD unimportant, but for the record the CI component means that you are making changes to your infrastructure in a test branch of your source code, testing it to make sure it works, and then merging the changes (assuming your tests passed) into your main branch. That merge part is what the “integration” is all about. You could stop there, but the CD component takes those changes and deploys them to your cloud environment. It makes the changes, or “delivers” them.

You could also say that CD “deploys” your changes. In fact, there’s not really an agreement if CD stands for continuous delivery or continuous deployment. Whichever you choose to go with is between you and your god.

Oh, and the “continuous” word means that all of this happens automatically or at least with minimal human interaction. So you’ll use Terraform Cloud Workspaces or CI/CD pipelines to do all this work for you. This blog will mostly be focusing on Terraform Cloud Workspaces that will make changes to your cloud infrastructure, like deploying new VMs. CI/CD pipelines will almost always be used to deploy custom software to your cloud infrastructure. If your company does not write software, you may never need to use CI/CD pipelines.

Terraform Cloud Workspaces

We’ll get to this in detail later, but it’s worth jumping ahead a bit. If you’re using the cloud you’re going to be deploying resources of some type to your infrastructure. In this blog, we’ll manage this using Terraform Cloud Workspaces. Terraform Cloud Workspaces will be part of your CI/CD process because you’ll be making changes to your IaC, merging those changes into Git, which will alert Terraform Cloud to update the infrastructure in the Terraform Cloud Workspace that has changed. Lots more to come on this!

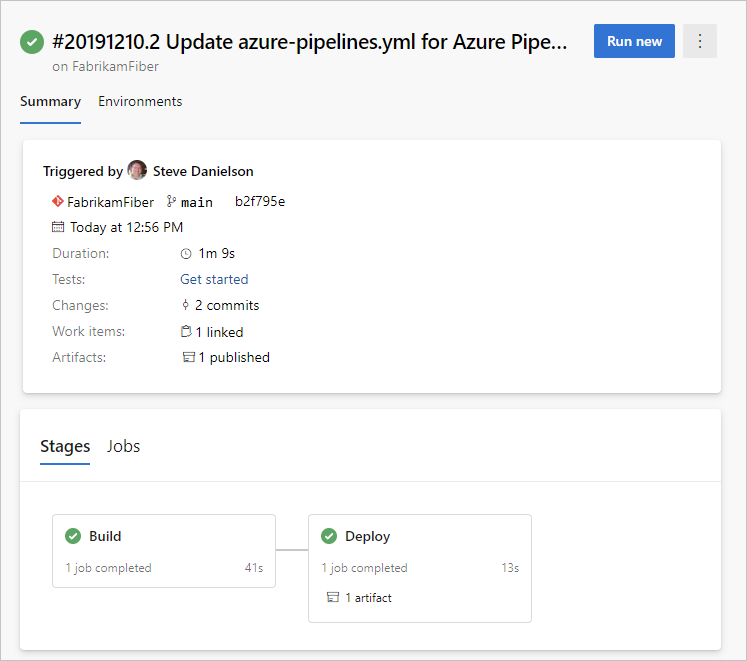

Pipelines

Pipelines can refer to a lot of things, but what I’m specifically talking about here are CI/CD pipelines. These are automated steps to release your software in a controlled, predictable manner. Pipelines simply do all the things you would do manually to deploy your changes, but do them in an automated way. They are called pipelines because the result of one step may determine what next step your pipeline takes. They can usually be visualized so you can easily see the steps that succeeded or failed.

For this section, we’re talking about CI/CD pipelines that deploy custom applications or software to your infrastructure. This usually only applies if you work at a company that developers software.

A common CI/CD pipeline for a test environment would be to perform the following steps.

- Build a software project from source code.

- Run unit tests.

- Deploy the build from the previous step to a test environment.

- Run integration tests (these are tests to ensure the new build will interact successfully with existing resources, like your database).

You could do all these manually, which you might do when you’re first spinning up your project. But doing these same steps every single time you have a new software update would be extremely time-consuming, which is why we use pipelines.

As per the CI/CD principles that I discussed, your pipelines can be “continuous” by automatically starting when something triggers them. For the pipeline above, you may want it to run the moment someone attempts to merge their branch into a the main branch, usually by something known as a pull request (PR). So when someone creates a PR, the PR will create a separate temporary branch that merges the code and runs the pipeline against that temporary branch. If the pipeline runs successfully, you can merge the code into the main branch. At that point you can manually run the production pipeline to deploy to your live environment, or if you really have your shit together, you can let the production pipeline run automatically after the test pipelines completes successfully.

There are plenty of great solutions for CI/CD pipelines, including Azure DevOps, Jenkins, Codefresh, and CircleCI. We’re going to be using GitHub Actions for this blog.

Environments

I’ve already referred to different environments without explaining them, but this is a pretty simple concept. An environment is a isolated or semi-isolated set of similar resources that are used in different stages of your deployment cycle. Your live environment is typically called your production environment. Unless your organization enjoys living on the edge of potential bankruptcy, you will have at least one environment for testing before you make changes to production. These environments may have different names, but here’s the most common structure.

| Environment Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Development | Resources where engineers may manually or automatically test their code against other services, like a database that is too large to store on a local workstation or prohibited by policy (such as HIPAA-compliant companies). This environment may be very volatile since different changes may be made frequently by different engineers but will give the engineer a decent idea if things are working before deploying to test. This environment is often skipped in a single-developer team and multiple development environments may exist for large teams. |

| Test | Resources where engineers deploy code to run automated tests. In a well-oiled team, this may be a dynamic environment that is created for the duration of the test and then destroyed. Usually only one software feature or update is deployed at a time. |

| Staging | Resources where engineers deploy changes to be reviewed by the stakeholders. In a software company, the product team would review this to make sure the changes meet their requirements as they understood them. This environment should be either the same release as production or one version ahead of it. |

| Production | Live environment. This is why you get paid. |

Each environment is expected to be as close to a logical mirror of production with each environment looking more similar to production as you go up. By “logical,” I mean the high-level architecture looks the same, but the redundancy and compute size will be smaller. So for production your database may have four nodes of redundancy and your web servers will be behind a load balancer, but in development you’ll have a single node for your database and web server, each being small-sized VMs.

Each environment should also have a security and/or network boundary between them. So to the degree you have control of the network, each one should be on a separate subnet with a firewall between them. Similarly, the services for each environment should run under different accounts. The point of all of this is to ensure that in case you do something dumb, like accidentally configure your test web server to connect to your production database, it simply won’t work. Also if one environment is hacked, the attack won’t spread as easily to the other environments.

Unit Testing

Unit tests aren’t squarely in the realm of platform engineering, but they are worth discussing because you’ll likely be incorporating them in your pipelines.

Unit testing mostly applies if you’re working at a software company. If you’re strictly in IT, this may not be that interesting. It’s also not interesting if you do work in a software company.

There are several ways to test code, and you’ll probably invoke many of them in your pipelines even if you aren’t writing the tests yourself. A unit test is a small chunk of code that developers write to test discrete logic. So let’s say part of a shopping cart on your web application is supposed to calculate sales tax. A developer would write a unit test that would test to ensure the sales tax of 8% for a given total of $18.75 would always result in the value of $1.50. The test would run at build time instead of a functional test afterward that would test that same functionality after the software is deployed to a server.

There are a few advantages that unit tests have over other tests. First, the way it’s supposed to work is that a developer writes the unit test first, then codes the actual logic. The thinking here is that the unit test would map directly to the requirements that are handed down from the product team, so writing that first would help guide the actual logic of the code. Secondly, the tests are repeatable and a way to ensure that something didn’t go screwy when the code is updated for a new feature. In the sales tax example, you’d be surprised how a change to some other part of code, say calculating the subtotal, may have some unintended effect on the other part. Unit tests catch these bugs early on.

In reality, not all developers start off writing unit tests. And some really hate writing unit tests and refuse to do it at all (if that is tolerated by the team). Writing tests aren’t the fun part of coding, and often things are discovered while writing the logic that make a developer have to change the unit test. Unit testing is very helpful to the overall development lifecycle, but its adoption will vary according to your work culture.

Other Words

These things are worth knowing about in case you’re stuck in the elevator with your CTO and need to have a halting, forced conversation.

Lean

Lean is a management style that is seeks to achieve continuous improvement by focusing on the value that the organization offers. It also has an emphasis on respecting people, both employees and customers, which is pretty cool.

Shift Left

If you tell your manager that you’re attempting to “shift left,” you may find a warm cookie and a cold glass of milk on your desk the next morning. The concept of shifting left is adopting good practices earlier in the development cycle, such as testing and security. Traditionally, these have been bolted on at the end, leaving software vulnerable.

For example, adding more unit tests at the beginning will catch bugs early in the process so your developers can fix them before they are even released to your test environment. On the security front, you may implement code scanners to catch things like SQL injections that can be difficult to test for later in the cycle.

All these frameworks, buzzwords, and methodologies can be overwhelming, so you’re forgiven if you have no shifts left to give at this point.

Comments